Why a progressive alliance is the key to renewal for the PvdA.

Across Europe, social democracy is in unprecedented decline. The French PS was irrelevant at last year’s presidential and parliamentary elections and in Germany’s recent general elections the SPD lost yet more ground to rivals left and right. While the Labour Party in the UK may look like an exception to the rule, its 2017 election result owed a great deal to tactical voting – a last-resort strategy adopted by voters whose first-preference candidate or party was effectively disqualified by the first-past-the-post voting system. This article focuses on the Netherlands, where local elections on 21 March resulted in yet another downturn for the Partij van de Arbeid (PvdA). It argues that much like progressives in the UK, the Dutch left needs a progressive alliance, and that building such a pact offers social-democrats a path back to political relevance.

Only 12 years ago the Dutch social-democrats of the PvdA enjoyed a resounding success in nationwide local elections, winning almost 25 percent of the overall vote, and celebrating victories in Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht. The party seemed to have overcome its difficult moment of the early 2000s, when large chunks of its traditional voter base had turned to populist parties instead.

Now, three electoral cycles on from that day, the PvdA has seen more than two-thirds of its vote share across the Netherlands evaporate – a fall from first to fifth among the national parties. Looking at the results of last week’s Dutch local elections, one would be tempted to think that their 2006 victory was their last. It may well have been.

While at the national level the collapse of the social democrats (in the 2017 general election) was abrupt and spectacular, their demise in local councils has been a gradual one. Take Amsterdam, where between 2006 and 2018 the PvdA went from 20 to 15 to 10 to 5 seats on the city’s 45-seat municipal council. The picture is similar (if less linear) in other places, and begs the question whether time is up for social democracy in the Netherlands.

The answer is both ‘yes’ and ‘no’.

Empty nest

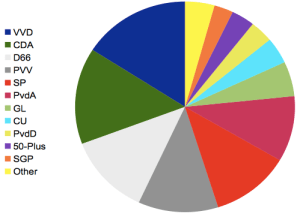

As a party in its own right, the PvdA has little hope of regaining its status as the leading force of the Dutch left. The proportional voting system in the Netherlands has bred a diverse – some would say fragmented – political landscape. Voter loyalty is low: the electorate has seen all kinds of ‘landslide’ election results for the best part of two decades, gradually tempting even the most risk-averse voter into reconsidering their options. All of this has eroded the appeal of a traditional broad-church social-democrat party, which today to many voters just looks bland.

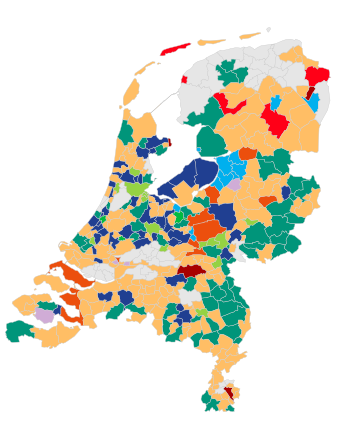

Map of the Netherlands showing the largest party per municipality (Image ANP)

In Amsterdam and Utrecht, cities with large populations of young, highly educated voters, the greens of GroenLinks were winners in last week’s local elections, receiving upwards of 20 percent of the vote. In Rotterdam and The Hague, where the ‘traditional working class’ electorate is bigger, victory went to local parties with populist roots. Denk, a new party speaking up for migrant communities, took multiple seats in all these cities’ councils. The list goes on, the picture is consistent: the voter constituencies formerly united in the social-democratic mainstream have branched out to new, bespoke political homes, leaving the PvdA a near-empty nest.

Green surge

While to some this may sound like a tragedy, it needn’t be. Sure, the demise of a largely progressive political party with all of its history, institutions, networks, and people represents a loss to Dutch politics and society. One that many, inside and outside the party, will continue to feel for some time to come. Nonetheless, the view from rock-bottom could be a hopeful one, as long as the Dutch social-democrats choose an inclusive path to renewal, one that recognises the challenges and opportunities of the wider progressive left, of which the PvdA used to be nucleus.

Nationally, Dutch progressives are on the back foot, and have been for some time. The so-called moderate parties of the right, as well as most media, are obsessed with anti-immigrant politicians, which the former shamelessly (and successfully) parrot for electoral gain. But it’s not all doom and gloom. While the left as a whole has contracted, the Dutch greens are breaking through into the mainstream, with GroenLinks winning big not just in university cities, but also in suburban areas and even in the industrial town of Helmond. All of this without diluting their message of rigorous economic reform, firm climate action, and welcoming refugees – a narrative previously associated with the electoral margins.

At the same time, the political emancipation of minority ethnic groups in the Netherlands has found a new vessel. Frustrated with barriers to representation within the mainstream parties, a group of non-white politicians broke away from the PvdA to form Denk, and quickly gathered a diverse following. Their agenda is a progressive one, mostly, and one that is finding a warm reception across migrant communities. While it is regrettable, of course, to find that the traditional parties have largely failed to empower migrant voices, the rise of Denk has the potential to improve the political representation and participation of people the traditional left was unable to reach.

Frans Timmermans (Image Elsevier).

The diverse progressive left in the Netherlands further includes a socialist party which has proven to be a potent left-wing alternative to divisive populists, and which boasts a wealth of networks and support especially in (post-)industrial communities. It includes a green protest party, which focuses on animal rights and has steadily grown since its inception 15 years ago. It has a good deal of common ground with the liberal democrats of D66 and the social protestant party, both of which are currently propping up the country’s centre-right government. And there’s the PvdA itself still, with all its political capital and its swathes of widely-respected politicians, from Frans Timmermans (European Commissioner) to Khadija Arib (Speaker of the House of Representatives) to Ahmed Aboutaleb (Mayor of Rotterdam).

Rainbow pact

Of course, the internal diversity of this landscape of progressive parties is not without challenges. But in a nation which has the consensus politics of coalition in its DNA, it should not be beyond progressive leaders to build on shared priorities and confront the regressive right in a more unified manner. This is where a renewed PvdA could prove itself essential, and where it could find a credible raison d’être: in being the broker and architect of a progressive answer to 17 years of cagy, reactive politics, dictated by fear of the likes of Fortuyn and Wilders.

The lure of governing, of delivering the Prime Minister, has always made the social democrats averse to entering into alliances with other, smaller, forces on the left. Now that the 2017 general election has decisively freed it from those shackles, and with no other progressive party naturally dominating the pack, it’s time for the PvdA (and indeed others on the left) to give serious thought to a common agenda that is brave and robust in its ambition, and firm in its rejection of the reactive right narrative. It would require progressive parties to agree and communicate the political direction before an election, then set the policy accents on the basis of the result.

If successful, such a ‘progressive rainbow pact’ could change politics for generations to come. Firstly, its success would demonstrate that right-wing populism can be beaten in a proportional system without pandering to its agenda of identity politics and fear. Secondly, it would show that a highly diverse political landscape, nurtured by the mechanics of proportional representation, can produce not only a stable governing force, but one that delivers bold progressive change, encompassing the priorities of a diverse electorate. This should be the destiny of social democracy in the Netherlands – and arguably across Europe.

This article was written for Compass and originally appeared here.

Dutch social democracy has hit rock bottom. Rejoice!

Why a progressive alliance is the key to renewal for the PvdA.

Across Europe, social democracy is in unprecedented decline. The French PS was irrelevant at last year’s presidential and parliamentary elections and in Germany’s recent general elections the SPD lost yet more ground to rivals left and right. While the Labour Party in the UK may look like an exception to the rule, its 2017 election result owed a great deal to tactical voting – a last-resort strategy adopted by voters whose first-preference candidate or party was effectively disqualified by the first-past-the-post voting system. This article focuses on the Netherlands, where local elections on 21 March resulted in yet another downturn for the Partij van de Arbeid (PvdA). It argues that much like progressives in the UK, the Dutch left needs a progressive alliance, and that building such a pact offers social-democrats a path back to political relevance.

Only 12 years ago the Dutch social-democrats of the PvdA enjoyed a resounding success in nationwide local elections, winning almost 25 percent of the overall vote, and celebrating victories in Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht. The party seemed to have overcome its difficult moment of the early 2000s, when large chunks of its traditional voter base had turned to populist parties instead.

Now, three electoral cycles on from that day, the PvdA has seen more than two-thirds of its vote share across the Netherlands evaporate – a fall from first to fifth among the national parties. Looking at the results of last week’s Dutch local elections, one would be tempted to think that their 2006 victory was their last. It may well have been.

While at the national level the collapse of the social democrats (in the 2017 general election) was abrupt and spectacular, their demise in local councils has been a gradual one. Take Amsterdam, where between 2006 and 2018 the PvdA went from 20 to 15 to 10 to 5 seats on the city’s 45-seat municipal council. The picture is similar (if less linear) in other places, and begs the question whether time is up for social democracy in the Netherlands.

The answer is both ‘yes’ and ‘no’.

Empty nest

As a party in its own right, the PvdA has little hope of regaining its status as the leading force of the Dutch left. The proportional voting system in the Netherlands has bred a diverse – some would say fragmented – political landscape. Voter loyalty is low: the electorate has seen all kinds of ‘landslide’ election results for the best part of two decades, gradually tempting even the most risk-averse voter into reconsidering their options. All of this has eroded the appeal of a traditional broad-church social-democrat party, which today to many voters just looks bland.

Map of the Netherlands showing the largest party per municipality (Image ANP)

In Amsterdam and Utrecht, cities with large populations of young, highly educated voters, the greens of GroenLinks were winners in last week’s local elections, receiving upwards of 20 percent of the vote. In Rotterdam and The Hague, where the ‘traditional working class’ electorate is bigger, victory went to local parties with populist roots. Denk, a new party speaking up for migrant communities, took multiple seats in all these cities’ councils. The list goes on, the picture is consistent: the voter constituencies formerly united in the social-democratic mainstream have branched out to new, bespoke political homes, leaving the PvdA a near-empty nest.

Green surge

While to some this may sound like a tragedy, it needn’t be. Sure, the demise of a largely progressive political party with all of its history, institutions, networks, and people represents a loss to Dutch politics and society. One that many, inside and outside the party, will continue to feel for some time to come. Nonetheless, the view from rock-bottom could be a hopeful one, as long as the Dutch social-democrats choose an inclusive path to renewal, one that recognises the challenges and opportunities of the wider progressive left, of which the PvdA used to be nucleus.

Nationally, Dutch progressives are on the back foot, and have been for some time. The so-called moderate parties of the right, as well as most media, are obsessed with anti-immigrant politicians, which the former shamelessly (and successfully) parrot for electoral gain. But it’s not all doom and gloom. While the left as a whole has contracted, the Dutch greens are breaking through into the mainstream, with GroenLinks winning big not just in university cities, but also in suburban areas and even in the industrial town of Helmond. All of this without diluting their message of rigorous economic reform, firm climate action, and welcoming refugees – a narrative previously associated with the electoral margins.

At the same time, the political emancipation of minority ethnic groups in the Netherlands has found a new vessel. Frustrated with barriers to representation within the mainstream parties, a group of non-white politicians broke away from the PvdA to form Denk, and quickly gathered a diverse following. Their agenda is a progressive one, mostly, and one that is finding a warm reception across migrant communities. While it is regrettable, of course, to find that the traditional parties have largely failed to empower migrant voices, the rise of Denk has the potential to improve the political representation and participation of people the traditional left was unable to reach.

Frans Timmermans (Image Elsevier).

The diverse progressive left in the Netherlands further includes a socialist party which has proven to be a potent left-wing alternative to divisive populists, and which boasts a wealth of networks and support especially in (post-)industrial communities. It includes a green protest party, which focuses on animal rights and has steadily grown since its inception 15 years ago. It has a good deal of common ground with the liberal democrats of D66 and the social protestant party, both of which are currently propping up the country’s centre-right government. And there’s the PvdA itself still, with all its political capital and its swathes of widely-respected politicians, from Frans Timmermans (European Commissioner) to Khadija Arib (Speaker of the House of Representatives) to Ahmed Aboutaleb (Mayor of Rotterdam).

Rainbow pact

Of course, the internal diversity of this landscape of progressive parties is not without challenges. But in a nation which has the consensus politics of coalition in its DNA, it should not be beyond progressive leaders to build on shared priorities and confront the regressive right in a more unified manner. This is where a renewed PvdA could prove itself essential, and where it could find a credible raison d’être: in being the broker and architect of a progressive answer to 17 years of cagy, reactive politics, dictated by fear of the likes of Fortuyn and Wilders.

The lure of governing, of delivering the Prime Minister, has always made the social democrats averse to entering into alliances with other, smaller, forces on the left. Now that the 2017 general election has decisively freed it from those shackles, and with no other progressive party naturally dominating the pack, it’s time for the PvdA (and indeed others on the left) to give serious thought to a common agenda that is brave and robust in its ambition, and firm in its rejection of the reactive right narrative. It would require progressive parties to agree and communicate the political direction before an election, then set the policy accents on the basis of the result.

If successful, such a ‘progressive rainbow pact’ could change politics for generations to come. Firstly, its success would demonstrate that right-wing populism can be beaten in a proportional system without pandering to its agenda of identity politics and fear. Secondly, it would show that a highly diverse political landscape, nurtured by the mechanics of proportional representation, can produce not only a stable governing force, but one that delivers bold progressive change, encompassing the priorities of a diverse electorate. This should be the destiny of social democracy in the Netherlands – and arguably across Europe.

This article was written for Compass and originally appeared here.

Leave a comment

Posted in Commentary, Democracy, Netherlands

Tagged democracy, Denk, elections, GroenLinks, politics, Progressive Alliance, PvdA